The main artistic work of pochoir ateliers in Paris in the

1910s was to reproduce facsimiles of manuscripts and paintings in limited

editions; they also added color to printed (phototypie) fashion plates in

fashion magazines. Many large printing

firms had a contingent of pocheurs in addition to an on-site bindery, like

Crété in Corbeil, the company that printed La

Prose du Transsibérien.

I wanted to work with pochoir again in my Typography class

at Scripps College, and so I invited Julie Mellby to give the Fall 2014

Frederic W. Goudy Lecture for the Scripps College Press on the history of

pochoir. She is the

graphic arts curator within Rare Books and Special Collections at Firestone

Library, Princeton University. Normally the Scripps College Press offers a workshop

to accompany the lecture. I thought it would be possible to reproduce a

Kandinsky painting in a small edition with the workshop participants. I was

still working on a timeline for the production of the pochoir for La Prose, and I hoped this experiment

might give me some clues.

In 1988, I had taken a pochoir workshop where we made the

stencils from acetate and worked with French pochoir brushes, so I taught the

workshop. My husband had mentioned that our Kandinsky calendar probably had a

good candidate for attempting a pochoir reproduction, so I chose the Landscape Near Murnau with Locomotive painting

from 1909.

|

| Kandinsky, Landscape Near Murnau with Locomotive, 1909 |

Since there would be fourteen participants, including Julie

Mellby, and there were fourteen colors in the painting, it would be a test to

see if we could produce an edition of sixteen copies in one day-long workshop.

|

| Workshop participants cutting stencils |

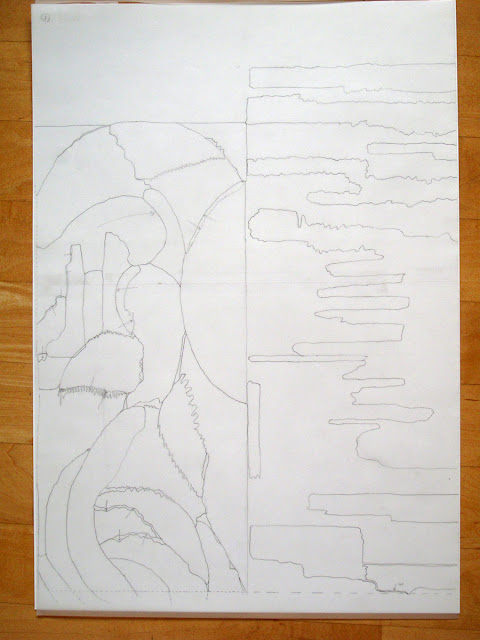

The first task is to identify all of the colors in the

painting and make a tracing.

|

| Tracing of the fourteen color areas |

You’re looking for areas that might need a

bridge; for example, if you have a donut shape, you have make a bridge from the

center circle to the outer circle to connect the two. I made color copies of

the painting and copies of the tracing so that each participant could choose a

color. A registration system with a three-hole punch was developed, where I

punched holes in both the Bristol paper and the acetate stencils.

Each participant had to mix their own gouache color to match

the color photocopy, and write down the recipe on a card.

|

| Gouache color swatches with recipes |

With a black

narrow marker, they traced their color areas onto acetate and then cut away

those areas with a knife.

|

| Knives used for cutting included Olfa (my favorite), X-acto, and inexpensive snap-off knives (above) |

I brought in several different kinds of knives

and let them choose whichever one worked well for them. It is difficult to cut

tight curves in acetate because the plastic pulls up while cutting, so they

practiced first.

The gouache is mixed to the consistency of milk in a

canister. We bought a double-cup holder for the gouache. You charge the fat

French pochoir brush with a small amount put into one cup and swirl it around

in the second cup. Then you test on scrap paper to make sure you are not too

wet. One of the challenges of editioning is to add just the right amount of

gouache to the brush each time you are ready to do the pochoir. Attach the

acetate stencil to the paper using the registration system and swirl lightly in

your color areas until you build up to the intensity of color desired.

|

| Swirl in a continuous circular fashion with the French pochoir brush |

If

your brush is too wet, the color will seep under the hole. The paper you use is

critical, since the paper could abrade easily if it is too soft. We used medium-weight

Bristol paper.

Normally each pocheur would complete the edition in her

color, and then go on to the next color in succession. But in this workshop,

the participants had different completion times because some pochoirs were more

complicated, so the order was random.

|

| Example mid-stream with eight colors |

|

| Example mid-stream with different colors completed |

We numbered the edition pages

to keep track. My press assistant, Chris Yuengling-Niles, made an accordion-fold

exemplar of all the colors in order.

|

| Progressive proofs in order by Chris Yuengling-Niles |

We completed all the pages by the end of the workshop,

hooray! But note that the cloud painting did not get done at the very end, so

the participants would have to finish that last area at home.

I knew from reading Jean Saudé’s 1925 book on pochoir, Traite d’enluminaire d’art au pochoir,

that they originally used metal stencils: copper, tin, zinc, pewter and

aluminum in various thicknesses. I wished that I could see one. I had gone

twice in 2014 to the Firestone Library at Princeton for research, and on the

second trip, I actually discovered one of Saudé’s copper pochoir stencils,

which was stunningly intricate. It had originally been included in the deluxe

edition of Saudé’s book and got separated until I found it in the collection.

You can see this amazing stencil in a Princeton blog post written by Julie Mellby. If you

want to read Saudé’s book in English, Havilah Press commissioned an English

translation of two sections of Saudé’s text, and published this in 2013 in a

limited edition, accompanied by an introduction outlining the history of

pochoir, two pochoir illustrations, and a list of references.

I had experimented with various thicknesses of copper and

aluminum for my own stencils for La Prose,

but even after reading Saudé in French, it was not clear how to cut into the

metal effectively. There is a drawing of the knife they used, the blade of which

is slightly curved. When I discovered that Atelier Coloris in France was using

the original techniques, I wrote to them and asked if they would work with me.

The next blog will be about the magnificent time I had in Ploubazlanec with

Nathalie Couderc and Christine Menguy, and how to cut and use the metal

stencils.